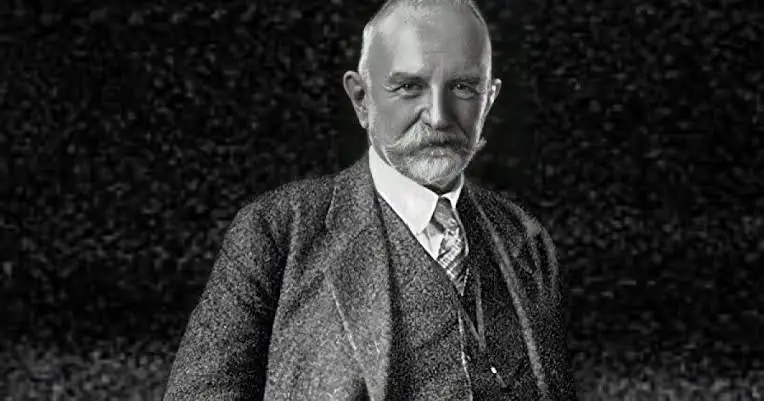

George Herbert Mead (1863-1931) is a major figure in Philosophy and (along with Willam James and John Dewey), is one of the founders of Pragmatism, a philosophical approach based on experimentation. Mead published numerous articles during his lifetime and several of his students produced four books in his name from his unpublished notes and stenographic records of his courses at the University of Chicago. Through his teaching, writing, and posthumous publications, Mead has exercised a significant influence in 20th Century social theory. Mead’s theory of the emergence of mind and self out of the social process of significant communication has become the foundation of the symbolic interactionist school of thought in philosophy.

George Herbert Mead is most well known for his theory of the self, which was presented in the 1934 book Mind, Self, and Society (published posthumously and edited by Charles W. Morris). Mead’s theory of personal identity maintains that the conception a person holds of themselves in their mind emerges from social interaction with others. This concept goes directly against the concept of biological determinism because it holds that an individual’s traits are not present at birth or fully present at the beginning of a social interaction, but are constructed and reconstructed in the process of social experience and activity.

The self, according to Mead, is made of two components: the “I” and the “me.” The “me” represents the expectations and attitudes of others (the “generalized other”) organized into a social self. From this point, the individual defines their own behavior with reference to the generalized attitude of the social groups they occupy. When the individual can view himself or herself from the standpoint of the generalized other, self-consciousness in the full sense of the term is attained. From this standpoint, the generalized other (internalized in the “me”) is the major instrument of social control, for it is the mechanism by which the community exercises control over the conduct of its individual members. On the other hand, the “I” is the response to the “me,” or the person’s individuality.

Within Mead’s theory, there are three activities through which the self is developed (language, play, and game). Language allows individuals to take on the “role of the other” and allows people to respond to his or her own gestures in terms of the symbolized attitudes of others. During play, individuals take on the roles of other people and pretend to be those other people in order to express the expectations of significant others. This process of role-playing is key to the generation of self-consciousness and to the general development of the self. In the game, the individual is required to internalize the roles of all others who are involved with him or her in the game and must comprehend the rules of the game.

Mead theorized that human beings begin their understanding of the social world through “play” and “game”. The “play” stage comes first in the child’s development. The child takes different roles they observe in society and play them out to gain an understanding of the different social roles. As a result, the child learns to become both subject and object and begins to become able to build a self. However, this is a limited self because the child can only take the role of distinct and separate others and still lack a more general and organized sense of themselves. In the game stage, a person is required to develop a full sense of self. Whereas in the play stage the child takes on the role of distinct others, in the game stage, the child must take the role of everyone else involved in the game. Furthermore, these roles must have a definite relationship to one another.

In the game stage, some form of social organization begins and defined personalities start to emerge. Individuals begin to become able to function in organized groups and determine what they will do within a specific group. Mead calls this the child’s first encounter with the “generalized other.” The “generalized other” can be thought of as understanding the given activity and the actors’ place within the activity from the perspective of all the others engaged in the activity. Through understanding the “generalized other” the individual understands what kind of behavior is expected and appropriate in different social settings.

It has been argued that social acts (such as games and routine forms of social interaction) enable perspective taking through ‘position exchange’ Assuming that games and routine social acts have differentiated social positions and that these positions create our cognitive perspectives, then it might be that by moving between roles in a game, we come to learn about the perspective of the other. This new interpretation of Mead’s account of taking the perspective of the other has experimental support.

In addition to his contributions in the realm of social philosophy, Mead is well known for his work on the philosophy of science. Mead sought to find the psychological origin of science in the efforts of individuals to attain power over their environment. The notion of a physical object arises out of a manipulatory experience. There is a social relation to inanimate objects, for the organism takes the role of things that it manipulates directly, or that it manipulates indirectly in perception. For example, in taking the resistant role of a solid object, an individual obtains cognition of what makes up nonliving things. Historically, the concept of the physical object arose from an animistic conception of the universe.

Contact experience includes experiences of position, balance, and support, and these are used by the organism when it creates its conceptions of the physical world. Our scientific concepts of space, time, and mass are abstracted from manipulatory experience. Such concepts as that of the electron are also derived from manipulation. In developing a science we construct hypothetical objects in order to assist ourselves in controlling nature. The conception of the present as a distinct unit of experience, rather than as a process of becoming and disappearing, is devised to facilitate exact measurement. In the scientific worldview, immediate experience is replaced by theoretical constructs. The ultimate in experience, however, is the manipulation and contact at the completion of an act.