Path dependency is a concept that illuminates how decisions made in the past, sometimes seemingly inconsequential at the time, cast long shadows over the present and future. It suggests that the trajectory of systems, whether in policy, culture, technology, or art, is not merely a product of current conditions but is deeply tethered to historical choices, which create inertia that can both guide and constrain future possibilities. Unlike a simple cause-and-effect model, path dependency emphasizes the compounding effects of early decisions, where initial conditions set a course that becomes increasingly difficult to deviate from, even when alternatives might be more efficient or desirable. This framework offers a nuanced lens through which to explore how legacy and inertia shape modern trajectories, particularly in the context of diaspora artists who grapple with redefining cultural identities while navigating the weight of historical narratives.

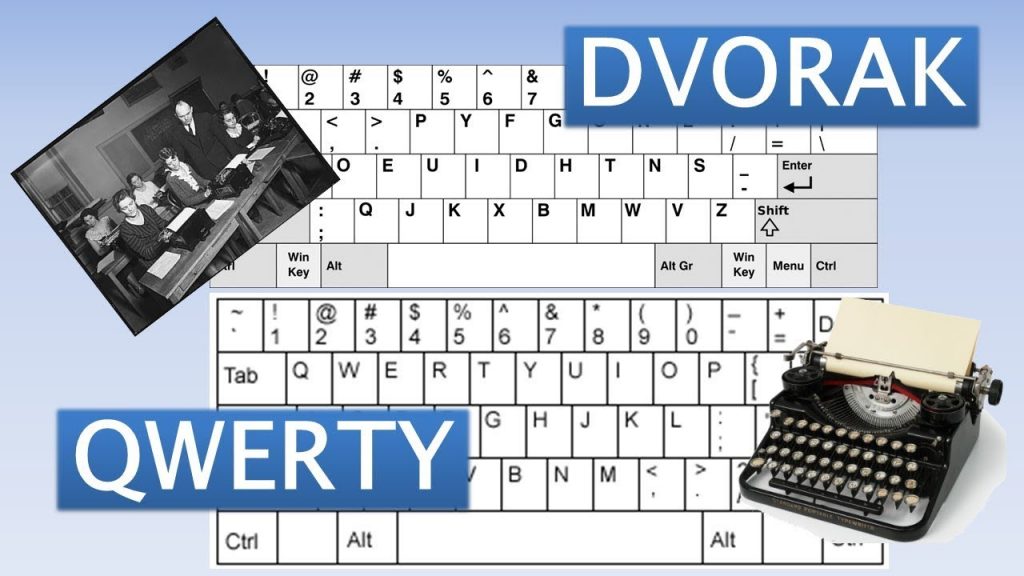

At its core, path dependency illustrates how systems evolve through a series of choices that lock in certain outcomes. In economics, the classic example is the QWERTY keyboard, designed in the 1870s to prevent typewriter jams by slowing typists down. Despite the advent of more efficient layouts like Dvorak, QWERTY’s early adoption by typewriter manufacturers, its standardization across industries, and the collective investment in learning it created a self-reinforcing cycle that entrenched its dominance. Switching to a new layout would require retraining millions and retooling production, making the cost of change prohibitive. This phenomenon, where historical choices create sticky systems, extends far beyond technology, influencing how societies, policies, and cultural identities evolve.

In American foreign policy in the Middle East, path dependence reveals how decisions made decades ago continue to shape contemporary challenges. The post-World War II strategy of the US to secure oil interests and counter Soviet influence led to alliances with authoritarian regimes, such as Saudi Arabia, and interventions like the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup in Iran. These choices established a pattern of prioritizing geopolitical stability over democratic ideals, creating a legacy of mistrust and anti-American sentiment in the region. The 2003 invasion of Iraq, for instance, can be seen as a continuation of this path, building on earlier interventions that normalized military presence and regime change as tools of influence. Each decision reinforced a trajectory where the US became entangled in complex regional dynamics, making it difficult to pivot toward diplomacy or disengagement without risking established interests. The inertia of these policies constrains modern options, as new administrations inherit alliances, enmities, and expectations shaped by decades of prior commitments.

Wider culture is also profoundly shaped by path dependency, often through the lens of retronyms, terms coined to distinguish older forms from newer iterations. Retronyms emerge when historical shifts force us to redefine what was once taken for granted. For example, the term “acoustic guitar” became necessary only after the invention of the electric guitar, just as “landline phone” emerged with the rise of mobile phones. These linguistic artifacts highlight how technological or cultural innovations can retroactively reshape our understanding of the past. In the context of path dependency, retronyms underscore how historical developments lock in certain cultural frameworks, making it challenging to revisit or reimagine earlier forms without the baggage of their successors. The term “traditional art,” for instance, gained prominence as digital and conceptual art forms proliferated, framing older practices as static or nostalgic, even when they remain vibrant and evolving.

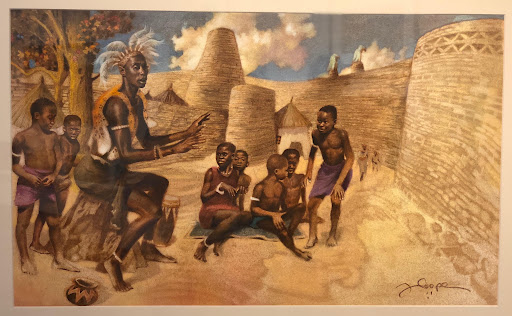

The dynamic of path dependency is particularly poignant for diaspora artists, whose work often grapples with the tension between inherited cultural legacies and the need to forge new identities in contemporary contexts. Historical migrations, whether forced or voluntary, create path-dependent cultural narratives that artists must navigate. For example, artists from the African diaspora may draw on ancestral traditions such as oral storytelling or textile patterns, which were shaped by centuries of resistance to colonialism and slavery. These traditions, while rich, carry the weight of historical trauma, and their integration into modern art can be constrained by expectations from both their communities and the broader art world. The inertia of these cultural paths, where certain symbols, motifs, or narratives become codified as “authentic,” can limit creative freedom, as artists risk being pigeonholeed or misunderstood when they deviate from expected forms.

Diaspora artists also demonstrate the potential to subvert path dependence by reclaiming and redefining their narratives. Consider the work of artists such as Yinka Shonibare, whose use of Dutch wax fabric, often mistaken as quintessentially African but a product of colonial trade routes, challenges assumptions about authenticity and cultural purity. By engaging with the historical paths that shaped these materials, Shonibare reimagines their meaning, turning a symbol of colonial exchange into a commentary on hybridity and globalization. Similarly, contemporary Indigenous artists like Kent Monkman use traditional forms like beadwork or painting alongside subversive, campy aesthetics to confront colonial legacies, breaking free from the path-dependent expectation that Indigenous art must adhere to romanticized notions of pre-colonial purity. These artists illustrate how path dependence can be both a constraint and a creative springboard, as they navigate the inertia of historical narratives while carving out new trajectories.

Technology offers another lens for understanding path dependence, where early standards shape entire industries. The dominance of Microsoft Windows in personal computing, for example, stems from decisions in the 1980s to license the operating system widely, creating a feedback loop where software developers prioritized Windows-compatible programs, which in turn attracted more users. This ecosystem became so entrenched that even superior alternatives struggled to gain traction. The legacy of these technological choices extends to cultural practices, as seen in the art world’s shift toward digital platforms. The rise of NFTs, for example, builds on the path-dependent infrastructure of blockchain technology, which prioritizes decentralization and market-driven valuation. While this has democratized access for some artists, it also constrains others who lack the resources or inclination to engage with digital markets, highlighting how technological paths can both enable and exclude.

In art, path dependency manifests in the canonization of certain styles or movements, which can overshadow alternative voices. The Western art historical canon, for instance, privileges Renaissance perspective and modernist abstraction, paths established through centuries of patronage and institutional support. These choices marginalize non-Western or non-linear art forms, such as Aboriginal dot painting or Islamic calligraphy, which follow distinct historical trajectories. Diaspora artists often find themselves navigating this tension, balancing the expectations of global art markets with the desire to honor their cultural roots. The inertia of the canon can make it difficult for these artists to gain recognition without conforming to established norms. Yet, their work also challenges the canon by introducing hybrid forms that defy traditional categorization.

The concept of path dependence also resonates with the broader theme of legacy in contemporary society. Historical decisions, whether in policy, culture, or art, create frameworks that are difficult to escape, yet they also provide the raw material for reinvention. Diaspora artists, in particular, embody this duality, as they inherit cultural identities shaped by migration, colonialism, and adaptation while forging new paths in globalized contexts. Their work highlights the challenges of reimagining cultural identities when history exerts such a powerful pull. By engaging with retronyms, whether linguistic or conceptual, these artists reveal how the past is never truly fixed but is constantly redefined by the present.

Path dependency offers a powerful framework for understanding how historical choices shape modern trajectories while also illuminating the possibilities for change. It reminds us that the present is not a blank slate but a tapestry woven from countless prior decisions, each thread reinforcing or challenging the ones before it. For diaspora artists, this lens underscores the complexity of their task: to honor the legacy of their histories while breaking free from the constraints of inertia, redefining their narratives in a world that is both bound by the past and open to reinvention.